Why E-Books Haven’t Replaced Paper Books: The Psychological Effect of Reading We Often Overlook

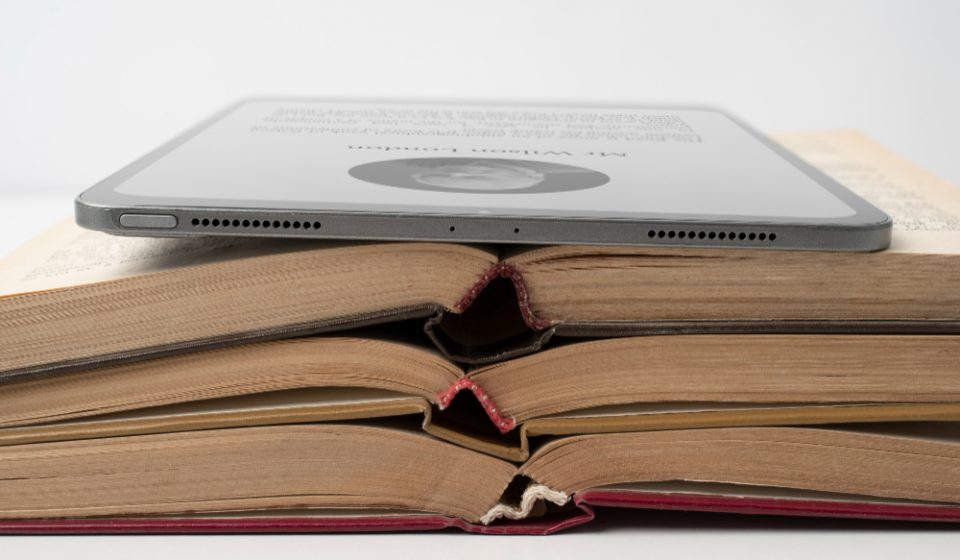

For more than two decades, digital technology has promised to revolutionize our relationship with reading. E-books arrived with the allure of instant access, portability, and sleek convenience. A single device could hold thousands of titles, sync across multiple screens, and weigh less than a paperback. Publishers and tech companies alike speculated that printed books would soon become relics of the past—beautiful, perhaps, but obsolete in a world defined by speed and minimalism.

Yet, despite all predictions, paper books have endured—and even thrived. Independent bookstores have experienced a resurgence. Print editions continue to outsell e-books in most major markets. And when readers are asked what format they prefer for immersive reading, the overwhelming response remains: the printed page. The question is, why?

The answer lies not only in nostalgia or aesthetic preference but in psychology. There’s something about the physical act of reading—a sensory, cognitive, and emotional ritual—that digital screens cannot quite replicate. The experience of holding a book, feeling its weight, smelling its paper, and physically tracking one’s progress through its pages activates mental processes that deepen comprehension and enhance retention in ways we rarely acknowledge.

In theory, reading is reading—words on a page, whether ink or pixels. But in practice, the brain experiences these two forms very differently. Research in cognitive psychology and neuroscience reveals that reading on paper engages both motor and spatial memory in ways that screens cannot. The tactile act of turning a page—the resistance of the paper, the sound it makes—anchors the text in physical space. We remember where a passage appeared in the book, how far we had read, and how far we had left to go. This creates a mental “map” of the story, allowing our brains to organize information more efficiently.

By contrast, the uniformity of digital pages erases this spatial awareness. On an e-reader, every “page” looks identical, and scrolling or tapping can create a sense of disorientation. This disrupts our ability to retain details and follow complex narratives. Studies have shown that readers often recall plot points less accurately after reading on screens compared to print. The difference is subtle, but its cumulative effect is significant, particularly when the goal is not just consumption, but comprehension.

Screen reading also invites a different state of mind. Digital devices are inherently multifunctional. Even on a dedicated e-reader, the very association with screens brings psychological cues of distraction. We are accustomed to screens as tools for skimming, scanning, and multitasking—not for lingering. This mindset can carry over into how we read digitally, encouraging faster, less reflective reading patterns. Paper, on the other hand, encourages stillness. The absence of notifications, hyperlinks, and brightness gradients grants us permission to sink fully into a text without external interruptions or the subtle mental pressure of connectivity.

Then there’s the sensory dimension—the feel, scent, and even sound of a physical book. These sensory cues do more than evoke sentimentality; they engage memory pathways. Just as certain smells can trigger vivid recollections, the specific physicality of a book becomes intertwined with the story itself. The slight yellowing of pages, the imprint of type, the dog-eared corners—all help ground reading as an embodied experience rather than a purely cognitive one. It’s not only about what we read, but how we hold and inhabit what we read.

The ritual of reading on paper also carries psychological weight. To open a book is to make a deliberate choice—a small act of commitment. The time it takes to find your place, to turn each page, creates rhythm and pacing that mirrors the unfolding of thought. E-books, by contrast, smooth out these small moments of friction, making reading more efficient but also more forgettable. Friction, paradoxically, helps memory. It slows us down just enough to let meaning take root.

In a culture obsessed with convenience, paper books offer an antidote: slowness, tangibility, and immersion. They remind us that reading is not merely a transaction of information but a human experience—deeply sensory, intimately personal, and psychologically rich. While digital formats will always have their place, particularly for travel, accessibility, and cost, they may never replace the quiet psychological satisfaction that a printed book provides.

Ultimately, the endurance of paper books is less about resisting technology and more about preserving the full texture of human cognition. Our brains, evolved long before screens, are wired to navigate and connect with the physical world. The printed page speaks that native language. Until technology can truly mimic the tactile, spatial, and emotional dimensions of paper, e-books will remain a complement, not a replacement—a convenience, not a companion.

And perhaps that is as it should be. In the relentless hum of the digital age, the rustle of a turning page still speaks to something timeless in us: the desire to hold a story not just in our minds, but in our hands.